Field scientists have discovered fossilized campfire remains of charred bones that provide evidence that pre-date Homo sapiens. These remains give evidence that while those humanoids may have learned to take advantage of naturally occurring fires more than one million years ago, they hadn’t figured out yet how to kindle a fire on their own.

The evidence that early humans had learned how to master fire and light are the images found in deep caves in Western Europe; the most famous of these being in Lascaux in southwestern France. These cave paintings date back about 15,000 to 30,000 years ago. The caves are so deep and narrow that no natural light can penetrate. An artificial light source would have been needed in order for those early humans to see well enough to paint. Experts postulate that early humans formed man-made depressions in stone and simply burned a few lumps of animal fat in them to provide light. As humans evolved, so too did their light sources.

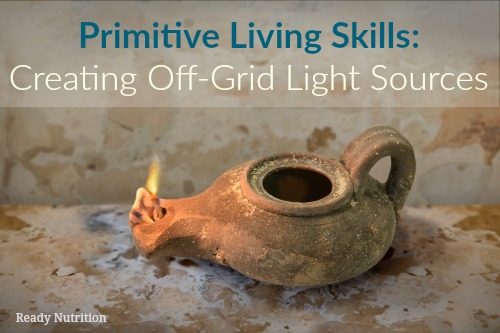

Primitive Lamps

Any non-flammable material with a depression to hold fuel can serve as a lamp: shells, bones, rocks, and clay. An example of this type of archaic lamp is a primitive clay “lamp”. This easy-to-make lamp would be a fun and educational project to do with kids. It’s important to use the right kind of clay. For this project, it’s best not to use modeling compounds that contain flour or plastic (Play-Doh and polymer clays, for example). Instead, use the type of clay found in the ground that is comprised of fine-grained natural rock or soil material. The best place to look for naturally occurring clay is along lakes, ponds, and the seashore. Conveniently, Amazon also has a wide selection here. Keep in mind that although this clay will become bone-dry on its own when exposed to air, it will remain brittle and easily broken unless it’s fired in a kiln. However, as long as care is taken not to break your creation, it will work very well for this project even without being fired.

Any non-flammable material with a depression to hold fuel can serve as a lamp: shells, bones, rocks, and clay. An example of this type of archaic lamp is a primitive clay “lamp”. This easy-to-make lamp would be a fun and educational project to do with kids. It’s important to use the right kind of clay. For this project, it’s best not to use modeling compounds that contain flour or plastic (Play-Doh and polymer clays, for example). Instead, use the type of clay found in the ground that is comprised of fine-grained natural rock or soil material. The best place to look for naturally occurring clay is along lakes, ponds, and the seashore. Conveniently, Amazon also has a wide selection here. Keep in mind that although this clay will become bone-dry on its own when exposed to air, it will remain brittle and easily broken unless it’s fired in a kiln. However, as long as care is taken not to break your creation, it will work very well for this project even without being fired.

A Cannan lamp is another example of primitive lighting. To make an open-bowl lamp like those used for the cave paintings, simply shape the clay into a shallow bowl shape, allow the clay to dry, and then place a small lump of fat or tallow in the depression of the bowl. To create a lightly more advanced lamp, create a lip along the edge of the bowl to hold a wick (think pour spout on a liquid measuring cup), The idea is to provide a reservoir for the oil and a depression along the lip of the bowl to support the wick upright.

To create an even more advanced lamp, you will need:

- Naturally occurring clay

- Water (to keep the clay moist while working it)

- A wick

- Olive oil or some other type of cooking oil.

Almost any shape will work as long as it has a hole for filling the lamp and a spout to hold the wick upright and a shape that keeps the oil from spilling out. The most commonly known shape for this type of lamp is the genie or Aladdin lamp.

Almost any shape will work as long as it has a hole for filling the lamp and a spout to hold the wick upright and a shape that keeps the oil from spilling out. The most commonly known shape for this type of lamp is the genie or Aladdin lamp.

Begin by shaping the clay into an ankle sock of elf shoe shape. Bring the “toe” of the shape upwards in order to support the wick. Create a hole for the wick in the end of the toe for the wick to protrude similar to the spout on a teapot. The larger hole, where if this were an elf shoe one’s ankle would be, is used for filling the lamp. At this point, a handle can be added to the lamp on the opposite end from the spout. It’s not necessary to make a lid for this lamp in order for it to work. Allow the clay to fully dry.

Next, you’ll need a wick. The size of the wick will depend on the size of your lap. You can make a primitive wick by braiding together strips of cotton cloth. Again, it’s important that you use natural cloth like cotton and not cotton-polyester blends. Pre-made cotton wicks can also be found here.

Pour the olive or cooking oil of your choice into the lamp and saturate your wick with the oil. Gently push the wick through the spout of the lamp (a wooden shish kabob stick works well) until most of your wick is resting in the reservoir of the lamp and only a small portion is sticking out the spout. Trim the wick if needed and light it. If the flame is too big, extinguish the flame and trim the wick again.

Candles

Candles can be made from a variety of waxes: animal, vegetable, and mineral waxes for example, or a combination of those waxes. The most commonly known animal wax is beeswax, but wax candles can also be made using tallow. Tallow candles are considered of lower-quality and less desirable than beeswax candles because they give off a sooty smoke when burned and an aroma similar to cooking they animal they came from. Vegetable waxes include soy and palm, among others. Mineral wax, or paraffin, is petroleum derived wax and is obtained during crude oil refining.

For this discussion, we’re going to concentrate on the most self-sufficient and desirable of the animal waxes- beeswax.

Beeswax is produced by worker bees of the genus apis. Honeybees (apis mellifera) produce beeswax in order to build the comb in their hives. When honey is harvested, either by the crush-and-drain method or by mechanical extraction, the leftover comb can be harvested and retained to produce beeswax candles.

Raw beeswax, fresh from the hive, bears little resemblance to the clean, purified beeswax beads one finds at craft stores. In order to make candles, the wax needs to be stripped of any leftover honey and debris in a process known as clarifying. A solar wax melter, like the one seen here, is an excellent way to clarify the wax. If you find that your wax still has undesirable particulates, simply heat the wax again using a double-boiler and pour through a fine woven cloth or coffee filter. (*Note: it’s important to keep your wax warm during the second clarification in order to keep it pouring through the filter. Otherwise, the wax will form a hard barrier on the filter and no wax will pour through). Beeswax burns at higher temperatures than paraffin wax and therefore needs a specific type of wick. Square braided cotton wicks that are about twice the thickness as those used for the same amount of paraffin are preferred. And like the oil lamp described earlier in this article, the size (diameter) of the wick used will be determined by the size and type of candle you plan on making.

Hand-dipped tapers can be made by simply tying a length of wick to a stick and dipping the wick repeatedly in the warm, melted beeswax. Patience is needed for this method in order to gain the desired thickness for the candle. Be sure the container holding the melted beeswax is deep enough to dip the entire length of the candle in without the wick folding or bending at any point.

Dip the wick once, allow it too cool for about 30 seconds until the wax becomes firm but not hard, and gently pull on the bottom of the wick to straighten it. This sets the wax for the shape your taper will take. Dip the wick quickly into the wax (wait too long and the wax that is already on the wick will begin to melt off back into the melted wax). Wait 30 seconds or so between dippings to allow the new layer of wax to firm up on the taper. Continue the dip/wait/dip/wait until the taper has reached the desired thickness to fit snugly in your candlestick.

Use the links below to learn more about the history of light and primitive methods

The History of Light, In 6 Minutes And 47 Seconds

History of Candles – Development and History of Candle Making

Learning to make primitive light sources is a fun and practical skill for all ages. Homemade beeswax tapers also make a wonderful gift for the upcoming holidays. Care should always be taken when using flammable products, especially when doing these types of projects with children.

Stay tuned!