It sounds like the stuff of horror films, nightmares, or scary bedtime stories.

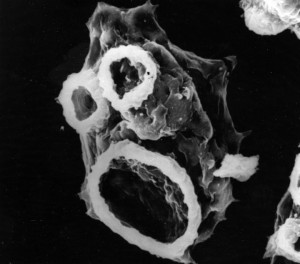

Unfortunately, Naegleria fowleri – more commonly known as “brain-eating amoeba” – is very real.

The amoeba lurks in warm freshwater lakes, rivers, and hot springs, and makes its way into the body via the nose when people go swimming or diving. According to the CDC, in very rare instances, Naegleria infections may also occur when contaminated water from other sources (such as inadequately chlorinated swimming pool water or heated and contaminated tap water) enters the nose.

Certain factors increase risk of exposure to the amoeba. From the CDC:

Naegleria fowleri is a heat-loving (thermophilic) organism. It grows best at higher temperatures up to 115°F (46°C) and can survive for short periods at higher temperatures. It is less likely to be found in the water as temperatures decline. The ameba can be found in lake or river sediment at temperatures well below where one would find the ameba in the water.

While infections with Naegleria fowleri are rare, they occur mainly during the summer months of July, August, and September. Infections are more likely to occur in southern-tier states, but can also occur in other more northern states. Infections usually occur when it is hot for prolonged periods of time, which results in higher water temperatures and lower water levels.

After Naegleria enters the nose, it travels to the brain, where it causes a swelling called primary meningoencephalitis (PAM). The infection leads to the destruction of brain tissue and is almost always fatal: it kills more than 97 percent of its victims within days. Only 3 people out of 132 known infected individuals in the United States from 1962 to 2013 have survived.

One of the 3 known survivors in the US is Kali Hardig, a 13-year-old from Benton, Arkansas, who was infected last summer after swimming at a water park. She was treated at Arkansas Children’s Hospital in Little Rock. Doctors there called the CDC and got a new drug to add to the cocktail they were already giving Kali. During the 22 days Kali was unconscious, doctors had to drill a hole in her skull to accommodate the swelling in her brain.

She’s made quite a recovery, as NBC News reports:

Kali completed her recovery with a combination of physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy, and began to regain what she’d lost. “Now she looks normal again,” Traci Hardig said. “She can talk and ride a bike, whatever.”

Kali was left with some scar tissue in her brain where the amoebae did their damage. But her brain has managed to rewire many of the connections she lost.

Infections are not common in the US, with only 34 cases reported between 2004 and 2013. Of those cases, 30 people were infected by contaminated recreational water, 3 people were infected after performing nasal irrigation (Neti pots) using contaminated tap water, and 1 person was infected by contaminated tap water used on a backyard slip-n-slide.

Naegleria infection usually occurs in people who have been engaging in water sports like diving, waterskiiing, or wakeboarding – activities that may forcefully suffuse the nose with lots of water.

Scientific American explained the progression of the infection:

It turns out that “brain eating” is actually a pretty accurate description for what the amoeba does. After reaching the olfactory bulbs, N. fowleri feasts on the tissue there using suction-cup-like structures on its surface. This destruction leads to the first symptoms—loss of smell and taste—about five days after the infection sets in.

Early symptoms usually start between 1 to 7 days after infection (usually in about 5 days) and resemble those of bacterial meningitis. Symptoms may include headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, and stiff neck. The neck stiffness is attributable to the inflammation, as the swelling around the spinal cord makes it impossible to flex the muscles.

As the infection spreads and penetrates more brain tissue, the secondary symptoms begin:

They include delirium, hallucinations, confusion and seizures. The frontal lobes of the brain, which are associated with planning and emotional control, tend to be affected most because of the path the olfactory nerve takes.

Loss of balance and lack of attention to people and surroundings are also observed.

“But after that there’s kind of no rhyme or reason—all of the brain can be affected as the infection progresses,” Jennifer Cope, an epidemiologist and expert in amoeba infections at the CDC, said.

After the start of symptoms, the disease progresses rapidly and usually causes death by respiratory failure within about 5 days (range 1 to 12 days).

Options for treatment are limited:

Several drugs are effective against Naegleria fowleri in the laboratory. However, their effectiveness is unclear since almost all infections have been fatal, even when people were treated with similar drug combinations. Recently, 2 people with Naegleria infection survived after being treated with a new drug called miltefosine that was given along with other drugs and aggressive management of brain swelling. (source)

If you suspect infection with Naegleria, seek medical care immediately, particularly if the person has been in freshwater recently and develop a sudden onset of fever, headache, stiff neck, and vomiting.

To prevent infection, experts say to assume there is a low level of risk associated with any warm freshwater, especially in southern states. Testing has shown the amoeba is commonly found in those bodies of water.

Evidence suggests infections may be increasing. Prior to 2010, more than half of cases came from Florida, Texas and other southern states. Since then, however, infections have popped up as far north as Minnesota.

Cope said, “We’re seeing it in states where we hadn’t seen cases before. It’s something we’re definitely keeping an eye on.”

Surveys in the 1970s found Naegleria fowleri in close to half the lakes in Florida. In 2011, two Australian researchers reviewed data from 18 countries in North America, Europe, and Asia and found overwhelming evidence that water towers and drinking-water systems were colonized with enough amoebas to be a health concern.

Avoiding the amoeba may be difficult because it is so common, so what can you do to avoid infection?

Cope told Scientific American that she recommends using nose plugs and not immersing your head fully under water when swimming. She also advises against kicking up sediment, which can shake the amoeba loose.

Naegleria is not found in salt water, like the ocean.

In June 2014, scientists sequenced the amoeba’s genome for the first time. Their insights may help us understand what makes it so virulent and point the way to better treatments.

This article was originally published at Ready Nutrition™ on July 22nd, 2014